A smooth Introduction to Portfolio Management

Introduction to Portfolio Management

In this short blog I am going to introduce the basics of portfolio

theory. It is an introduction to a set of blogs dedicated to

portfolio choices that focus on long holding

periods. In particular, these periods are between 10 and 30

years. Several studies revealed that frequently switching between funds

leads investors to withdraw from and invest into the market at wrong

times. This implies that market-timing does not work for the average

investor. Dalbar for instance, publishes continuous reports on “Quantitative

Analysis of Investor Behavior” that support the idea that short-term

investing might lead to make the exact wrong decision. The definitions

below will help to build methodologies for a systematic approach to

investing. I will try to keep everything as short as possible.

So

lets start with the risk-return tradeoff, which is the

principle that expected return rises with an increase in risk. Thus, an

investor can expect higher profits only if the investor is willing to

accept the possibility of higher losses. Markowitz (1991) shows how to

maximize expected return for a given level of variance. He assumes that

investors prefer asset A over B with same expected return, whenever

asset A has a smaller variance than asset B.

Definitions

In order to get a logical understanding of the topic and developing it further, we need to make some definitions that will be referred to across posts. First and foremost, the portfolio return is defined as: \[ r_p = \sum_{i=1}^n w_i r_i = w'r \] with weights summing up to 1: \[ \sum_{i=1}^n w_i = w' 1\]

The expected return of a portfolio is \[\mu_p = \mathop {\mathbb E}[r_p] =

\sum_{i=1}^n w_i \mathop {\mathbb E}[r_i] = w' \mathop {\mathbb

E}[r]\] and the corresponding variance of the portfolio

return is: \[ \sigma_p^2 =

\sum_{i=1}^n w_i^2 \sigma_i^2 + \sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{i\neq j} w_i

w_j Cov[r_i, r_j] = w'\Sigma w\]

Diversification

The last equation reveals that portfolio risk consists of two

components. The first part is called idiosyncratic

risk and is almost fully diversifiable. In general,

diversification is a technique that reduces risk by allocating

investments among various financial instruments, industries, and other

categories. It aims to maximize return by investing in different areas

or assets that are expected to move in different directions given a

specific shock. As a result, idiosyncratic risks are

risks specific to a company, industry, market, economy, or country are

reduced, if not eliminated. The concept of diversification can also be

shown by a mathematical proof, which is derived in only one line.

Proof:

For this purpose we assume a zero covariance, meaning that the

correlation between assets is zero. If we use an equally weighted

portfolio, such that \(w_i = 1/n\),

then the portfolio’s variance will converge to zero as n goes to

infinity. Most ETFs on indices however are value-weighted and

automatically introduce exposure to a value risk premium, which might

not be intended by the investor. In particular, the proof below would

also hold for a value-weighted portfolios as the weights would be a

function of individual market capitalization and \(n\), such that \((w_i = MC_i/(\overline{MC}\cdot n)\). Thus

the portfolio variance converges slower to 0 as \(n\) grows linearly instead of

exponentially.

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \sigma_p^2 = \lim_{n

\rightarrow \infty} \sum_{i=1}^n \frac{ \sigma_i^2} {n^2} +

\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{i\neq j} \frac{ 0} {n^2}= 0\] We can see that

it is desirable to benefit from the diversification

effect which reduces portfolio risk.

Geometric Proof:

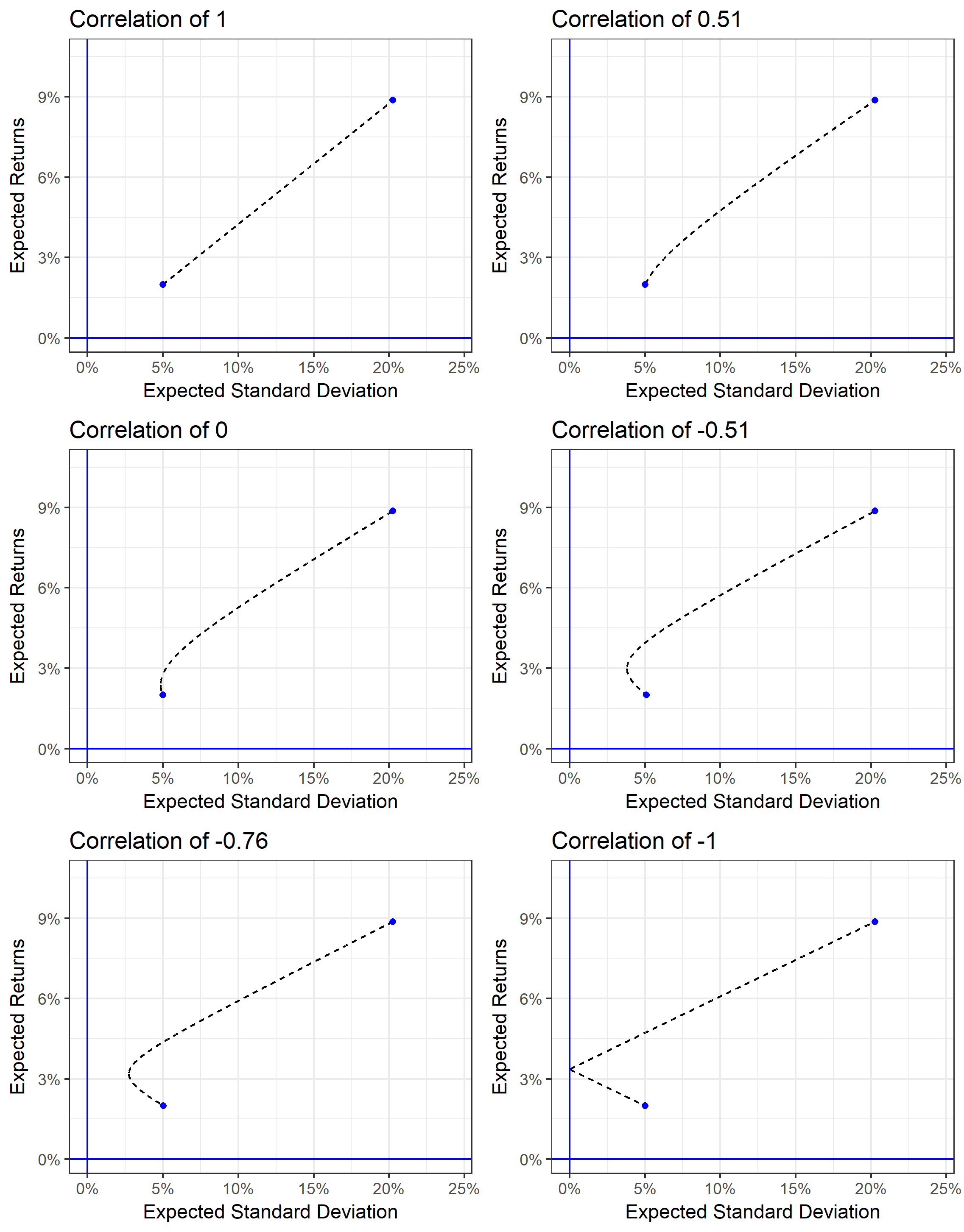

The second part of the portfolio variance is the weighted covariance. This part can also be represented by entries of the correlation matrix multiplied by the standard deviation. Hence, any correlation contributes positively or negatively to the overall portfolio risk. For illustration purposes consider the plot below: It shows two assets with various return correlations. The blue dots indicate a full investment in either one of the two assets. Further, the dashed line indicates all possible portfolios constructed by these two assets. Only if the correlation is perfectly negative, the portfolio risk will be zero.

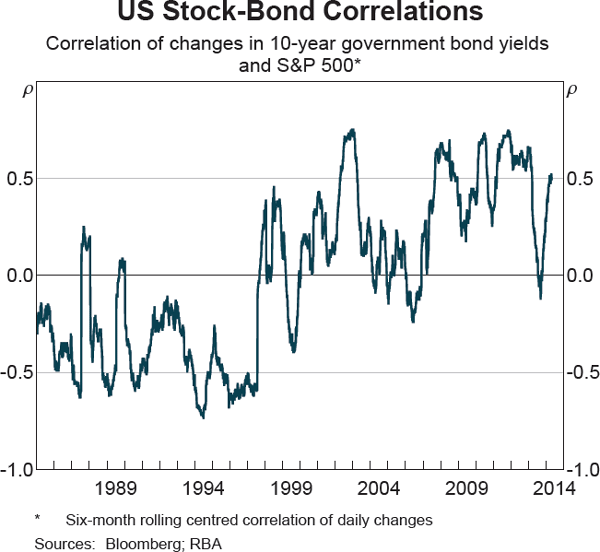

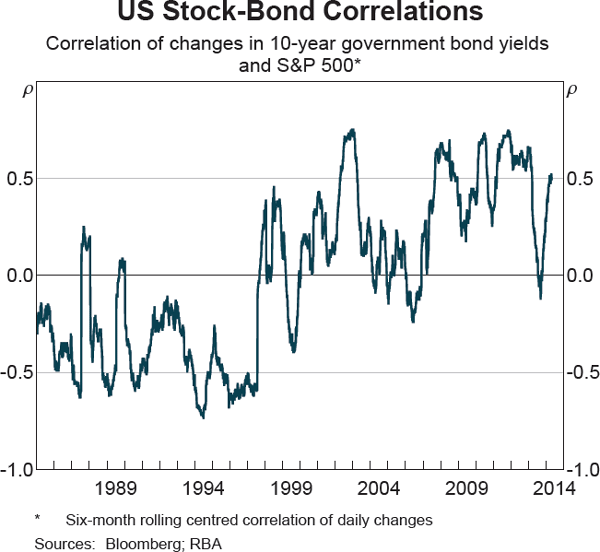

Unfortunately, zero correlations across assets are unobservable (see

also US Stock-Bond plot) and thus, the second part of the portfolio

variance is unequal to zero. In general, systematic

risks are variations in inflation rates and exchange rates,

political and economic instability, war, and interest rate changes,

which is undiversifiable. Nonetheless, the latter risk

component is supposed to be priced in financial markets and is the

compensation for bearing systematic risks. This compensation is known as

the risk premium or discount rate. These discount rates

are time varying as a result of time variation in the underlying

portfolio return correlations. Idiosyncratic risk on the other hand, is

not compensated as it is diversifiable.

Obviously, if the

last part is negative, the entire variation is smaller, which is the

main idea of the 60/40 asset allocation rule that invests in stocks and

bonds. The idea thereby is that the two asset classes generally move in

opposite directions and are thus negatively correlated. Unfortunately,

since 1999, the negative relationship has turned positive for long-term

holdings as plotted above.

Fortunately, a very large set of different approaches exists that try

to implement low correlations with the market and simultaneously take

advantage of the diversification effect. Some of these methodologies are

discussed in later sections. These examples try to optimize the

trade-off between risk and return, but also wrt higher moments. Some of

these methods also consider reduced transaction costs by decreasing the

turnover or the number of assets n as there exists an obvious trade-off

between high diversification, implying a large number of assets \(n\), and fees.

Before we jump to MV

estimation we should mention the behavior of discount rates.

Surprisingly, it turned out that expected stock returns are

time-varying in contrast to the view of the 1970s. As a

consequence, discount rate variation over time and across assets has

replaced informational efficiency as the central

organizing question of asset pricing. Several arguments try to explain

the time variation:

- Campbell and Cochrane (1999): time-varying risk aversion

- Bansal and Yaron (2004): time-varying diffusive risk

- Wachter (2013): time-varying disaster risk

Although, we are not completely confident what causes time-variation, we should bear in mind that expectations estimated via the short to medium run might be better approximations for expected returns than long run measures.